Table partitioning in SQL Server is essentially a way of making multiple physical tables (row sets) look like a single table. This abstraction is performed entirely by the query processor, a design that makes things simpler for users, but which makes complex demands of the query optimizer.

This post looks at two examples which exceed the optimizer’s abilities in SQL Server 2008 onward.

1. Join Column Order Matters

This first example shows how the textual order of ON clause conditions can affect the query plan produced when joining partitioned tables. To start with, we need a partitioning scheme, a partitioning function, and two tables:

CREATE PARTITION FUNCTION PF (integer)

AS RANGE RIGHT

FOR VALUES

(

10000, 20000, 30000, 40000, 50000,

60000, 70000, 80000, 90000, 100000,

110000, 120000, 130000, 140000, 150000

);

GO

CREATE PARTITION SCHEME PS

AS PARTITION PF

ALL TO ([PRIMARY]);

GO

CREATE TABLE dbo.T1

(

c1 integer NOT NULL,

c2 integer NOT NULL,

c3 integer NOT NULL,

CONSTRAINT PK_T1

PRIMARY KEY CLUSTERED (c1, c2, c3)

ON PS (c1)

);

GO

CREATE TABLE dbo.T2

(

c1 integer NOT NULL,

c2 integer NOT NULL,

c3 integer NOT NULL,

CONSTRAINT PK_T2

PRIMARY KEY CLUSTERED (c1, c2, c3)

ON PS (c1)

);

Next, we load both tables with 150,000 rows. The data does not matter very much. This example uses a “numbers” table containing all the integer values from 1 to 150,000. Both tables are loaded with the same data.

INSERT dbo.T1

WITH (TABLOCKX)

(c1, c2, c3)

SELECT

N.n * 1,

N.n * 2,

N.n * 3

FROM dbo.Numbers AS N

WHERE

N.n BETWEEN 1 AND 150000;

GO

INSERT dbo.T2

WITH (TABLOCKX)

(c1, c2, c3)

SELECT

N.n * 1,

N.n * 2,

N.n * 3

FROM dbo.Numbers AS N

WHERE

N.n BETWEEN 1 AND 150000;

Test query

Our test query performs an inner join of these two tables. Again, the query is not important or intended to be particularly realistic. It is used to demonstrate an odd effect when joining partitioned tables.

The first form of the query uses an ON clause written in c3, c2, c1 column order:

SELECT *

FROM dbo.T1 AS T1

JOIN dbo.T2 AS T2

ON T2.c3 = T1.c3

AND T2.c2 = T1.c2

AND T2.c1 = T1.c1;

The execution plan produced for this query (on SQL Server 2008 to SQL Server 2014) features a parallel hash join, with an estimated cost of 2.6953:

This is a bit unexpected. Both tables have a clustered index in c1, c2, c3 order, partitioned by c1, so we would expect a merge join, taking advantage of the index ordering.

Let’s try writing the ON clause in c1, c2, c3 order instead:

SELECT *

FROM dbo.T1 AS T1

JOIN dbo.T2 AS T2

ON T2.c1 = T1.c1

AND T2.c2 = T1.c2

AND T2.c3 = T1.c3;

The execution plan now uses the expected merge join, with an estimated cost of 1.64119 (down from 2.6953). The optimizer also decides that it is not worth using parallel execution:

Merge join query hint

Noting that the merge join plan is clearly more efficient, we can attempt to force a merge join for the original ON clause order using a query hint:

SELECT *

FROM dbo.T1 AS T1

JOIN dbo.T2 AS T2

ON T2.c3 = T1.c3

AND T2.c2 = T1.c2

AND T2.c1 = T1.c1

OPTION (MERGE JOIN);

The resulting plan does use a merge join as requested, but it also features sorts on both inputs, and goes back to using parallelism. The estimated cost of this plan is 8.71063:

Both Sort operators have the same properties:

Optimizer bug

The optimizer thinks the merge join needs its inputs sorted in the strict written order of the ON clause, introducing explicit sorts as a result.

The optimizer is aware that a merge join requires its inputs sorted in the same way, but it also knows that the column order does not matter. Merge join on c1, c2, c3 is equally happy with inputs sorted on c3, c2, c1 as it is with inputs sorted on c2, c1, c3 or any other combination.

Unfortunately, this reasoning is broken in the query optimizer when partitioning is involved. This is an optimizer bug that has been fixed in SQL Server 2008 R2 and later.

Trace flag 4199 is required to activate the fix prior to SQL Server 2016:

SELECT *

FROM dbo.T1 AS T1

JOIN dbo.T2 AS T2

ON T2.c3 = T1.c3

AND T2.c2 = T1.c2

AND T2.c1 = T1.c1

OPTION (QUERYTRACEON 4199);

You would normally enable this trace flag using DBCC TRACEON or as a start-up option, because the QUERYTRACEON hint is not documented for use with 4199. The trace flag is required in SQL Server 2008 R2, SQL Server 2012, and SQL Server 2014.

SQL Server 2008

There is no fix for SQL Server 2008, the workaround is to write the ON clause in the ‘right’ order! If you encounter a query like this on SQL Server 2008, try forcing a merge join and look at the sorts to determine the ‘correct’ way to write your query’s ON clause.

SQL Server 2005

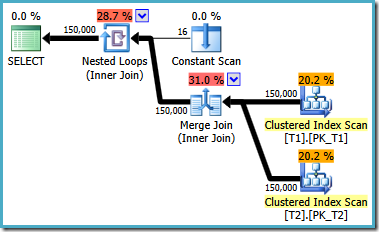

This issue does not arise in SQL Server 2005 because that release implemented partitioned queries using an APPLY model:

The SQL Server 2005 query plan joins one partition from each table at a time, driven from an in-memory table (the Constant Scan) containing the partition numbers to process. Each partition is merge joined separately on the inner side of the join. The 2005 optimizer is smart enough to see that the ON clause column order does not matter.

This is an example of a collocated merge join, a facility that was lost when moving from SQL Server 2005 to the new partitioning implementation in SQL Server 2008. A suggestion on Connect to reinstate collocated merge joins was closed as Won’t Fix.

2. Group By Order Matters

The second peculiarity I want to look at follows a similar theme, but relates to the order of columns in a GROUP BY clause. We will need a new table to demonstrate:

CREATE TABLE dbo.T3

(

RowID integer IDENTITY NOT NULL,

UserID integer NOT NULL,

SessionID integer NOT NULL,

LocationID integer NOT NULL,

CONSTRAINT PK_T3

PRIMARY KEY CLUSTERED (RowID)

ON PS (RowID)

);

GO

INSERT dbo.T3

WITH (TABLOCKX)

(UserID, SessionID, LocationID)

SELECT

ABS(CHECKSUM(NEWID())) % 50,

ABS(CHECKSUM(NEWID())) % 30,

ABS(CHECKSUM(NEWID())) % 10

FROM dbo.Numbers AS N

WHERE

N.n BETWEEN 1 AND 150000;

The table has an aligned nonclustered index, where ‘aligned’ means it is partitioned in the same way as the base object:

CREATE NONCLUSTERED INDEX nc1

ON dbo.T3 (UserID, SessionID, LocationID)

ON PS (RowID);

Test query

Our test query groups data on the three nonclustered index columns and returns a count for each group:

SELECT

T3.LocationID,

T3.UserID,

T3.SessionID,

COUNT_BIG(*)

FROM dbo.T3 AS T3

GROUP BY

T3.LocationID,

T3.UserID,

T3.SessionID;

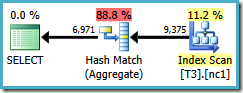

The query plan scans the nonclustered index and uses a Hash Match Aggregate to count rows in each group:

There are two problems with Hash Aggregate:

- It is a blocking operator. No rows are returned until all input rows have been aggregated.

- It requires a memory grant to hold the hash table.

Stream aggregate

In many real-world scenarios, we would prefer a Stream Aggregate here because that operator is only blocking per group, and does not require a memory grant. The client application would start receiving data earlier, would not have to wait for memory to be granted, and SQL Server can use that memory for other purposes.

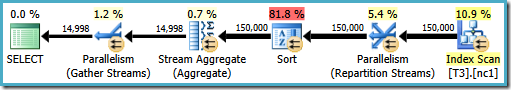

We can require the query optimizer to use a Stream Aggregate for this query by adding an OPTION (ORDER GROUP) query hint. This results in the following execution plan:

The sort operator

The Sort operator is fully blocking and also requires a memory grant, so this plan appears to be worse than using a Hash Aggregate. But why is the sort needed? The properties show that the rows are being sorted in the order specified by our GROUP BY clause:

This sort is expected because partition-aligning the index means the partition number is added as a leading column of the index (for SQL Server 2008 onward). In effect, the nonclustered index keys are (partition_id, user, session, location) due to the partitioning. Rows in the index are still sorted by user, session, and location, but only within each partition.

Single partition

If we restrict the query to a single partition, the optimizer ought to be able to use the index to feed a Stream Aggregate without sorting. In case that requires some explanation, specifying a single partition means the query plan can eliminate all other partitions from the nonclustered index scan, resulting in a stream of rows that is ordered by (user, session, location).

We can achieve this partition elimination explicitly using the $PARTITION function:

SELECT

T3.LocationID,

T3.UserID,

T3.SessionID,

COUNT_BIG(*)

FROM dbo.T3 AS T3

WHERE

$PARTITION.PF(T3.RowID) = 1 -- New!

GROUP BY

T3.LocationID,

T3.UserID,

T3.SessionID;

Unfortunately, this query still uses a Hash Aggregate, with an estimated plan cost of 0.287878:

The scan is now just over one partition, but the (user, session, location) ordering has not helped the optimizer use a Stream Aggregate. You might object that (user, session, location) ordering is not helpful because the GROUP BY clause is (location, user, session), but the key order does not matter for grouping.

Adding an ORDER BY

Let’s add an ORDER BY clause in the order of the index keys to prove the point:

SELECT

T3.LocationID,

T3.UserID,

T3.SessionID,

COUNT_BIG(*)

FROM dbo.T3 AS T3

WHERE

$PARTITION.PF(T3.RowID) = 1

GROUP BY

T3.LocationID,

T3.UserID,

T3.SessionID

ORDER BY -- New!

T3.UserID ASC,

T3.SessionID ASC,

T3.LocationID ASC;

Notice that the ORDER BY clause matches the nonclustered index key order, even though the GROUP BY clause does not.

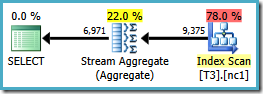

The execution plan for this query is:

Now we have the Stream Aggregate we were after, with an estimated plan cost of 0.0423925. This is much lower than the 0.287878 cost of the Hash Aggregate plan (by almost a factor of seven).

Reordering the GROUP BY

The other way to achieve a Stream Aggregate is to reorder the GROUP BY columns to match the nonclustered index keys:

SELECT

T3.LocationID,

T3.UserID,

T3.SessionID,

COUNT_BIG(*)

FROM dbo.T3 AS T3

WHERE

$PARTITION.PF(T3.RowID) = 1

GROUP BY

T3.UserID,

T3.SessionID,

T3.LocationID;

This produces the same Stream Aggregate plan with exactly the same cost.

Ordering issues

The sensitivity to GROUP BY column order is specific to partitioned table queries in SQL Server 2008 and later.

You may recognize that the root cause of the problem here is similar to the previous case involving a Merge Join. Both Merge Join and Stream Aggregate require input sorted on the join or aggregation keys, but neither cares about the order of those keys. A Merge Join on (x, y, z) is just as happy receiving rows ordered by (y, z, x) or (z, y, x) and the same is true for Stream Aggregate.

Distinct

This optimizer limitation also applies to DISTINCT in the same circumstances. The following query results in a Hash Aggregate plan with an estimated cost of 0.286539:

SELECT DISTINCT

T3.LocationID,

T3.UserID,

T3.SessionID

FROM dbo.T3 AS T3

WHERE

$PARTITION.PF(T3.RowID) = 1;

If we write the DISTINCT columns in the order of the nonclustered index keys:

SELECT DISTINCT

T3.UserID,

T3.SessionID,

T3.LocationID

FROM dbo.T3 AS T3

WHERE

$PARTITION.PF(T3.RowID) = 1;

…we are rewarded with a Stream Aggregate plan with a cost of 0.041455:

Summary

This is a limitation of the query optimizer in SQL Server 2008 and later (including SQL Server 2019) that is not resolved using trace flag 4199 (as was the case for the first example).

The problem only occurs with partitioned tables with a GROUP BY or DISTINCT over three or more columns using an aligned partitioned index, where a single partition is processed.

As with the Merge Join example, this represents a backward step from the SQL Server 2005 behaviour. SQL Server 2005 did not add an implied leading key to partitioned indexes, using an APPLY technique instead.

In SQL Server 2005, all the queries presented here using $PARTITION to specify a single partition result in query plans that performs partition elimination and use a Stream Aggregate without any query text reordering.

Final Thoughts

The changes to partitioned table processing in SQL Server 2008 improved performance in several important areas, primarily related to the efficient parallel processing of partitions. Unfortunately, these changes had side effects which have not all been resolved in later releases.

No comments:

Post a Comment

All comments are reviewed before publication.